Setting a Fair Price: It’s All about You

This post originally appeared on The ATA Chronicle and it is republished with permission.

We are freelancers. We don’t need to maximize profits for invisible stockholders, who tend to only care about their dividends or capital gains and not a whit about language or what we do. For us, the definition of being rich is not to want for anything. We don’t define our wealth in terms of having more toys than the next person. Therein lies the secret to what I call breakeven pricing: making enough money for ourselves and not worrying about whether anyone else is making more or less.

A simple definition underlies what this article is about: the breakeven point is that price above which we are making a profit and below which we are losing money. In other words, the cost of delivering the product or service equals the money taken in for delivering it.

To price any product or service, one simply has to charge more than the breakeven point. How much more is completely irrelevant. This is because if we have calculated the breakeven point correctly, we don’t want any more; the profit is only a safety margin (accountants call it the “gross operating margin”).

In absolute terms, every transaction (whether a translation, an interpreting assignment, or even a piece of pottery at a craft fair) has its own unique breakeven point because the costs of each transaction differ over time, along with the countless variables that go into it. We could go nuts trying to calculate that. Fortunately, we don’t have to. Here are some simple steps to help you calculate your breakeven point.

Step 1: Add Up Everything You Want or Need—Everything

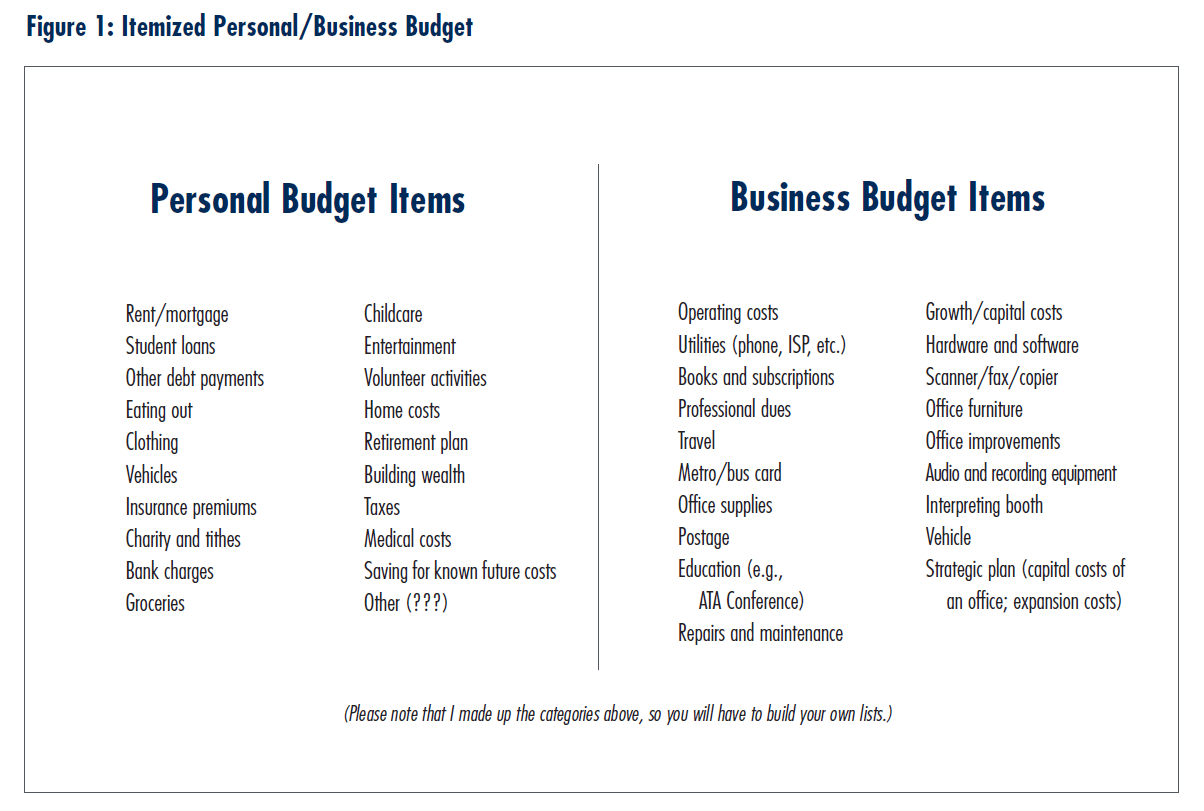

Do this for one year. Include what life is costing you now, but also everything you want for the future. Do this for yourself and your family. Involve your partner and family, and especially anyone who is or may soon be contributing to the family budget. After you make your personal budget list, it’s time to make one for your business. You really should develop a business plan so you know where you want to take your business, but that is the subject for another day. For this first time, just imagine what your business needs to run the way it should, especially if you know you need some items that you don’t have now. (See Figure 1 below for a sample itemized budget.)

Now, add it all up. This is not the time to worry about whether you can afford it or earn enough. This step is for dreams. After all, a plan is just a dream with a due date. You have to start with the dream.

Step 2: Figure Out How Much Time You Have to Make the Money in Step 1

Generally, there are about 2,000 working hours in a year. That assumes an eight-hour workday and a two-week vacation. Human resources experts use 2,000 to figure hourly wages in their heads. For example, $25/hour equals $50,000/year; the minimum wage is only $7.25/hour, which equals $14,500/year.

The problem is that you cannot work 2,000 hours in a year. There are holidays, and you get sick sometimes. As freelancers, we can take time off for more important things than our jobs, but we have to subtract those hours. As an example, a public sector job in Virginia would give you 11 holidays (88 hours) and 80-120 hours of sick leave. That would take 10% (200 hours) off your 2,000 hours right there.

Also, you cannot work on billable, paying jobs all of the time. You have to run your business: get the mail, deposit checks, attend conferences, meet with clients, travel, etc. It’s valid work time, but you cannot assign it to any one client, so it becomes a business expense that is not reimbursed. We call this overhead (or indirect costs). You make each client pay their fair share by taking those hours out of the equation so that your rate goes up enough to cover the overhead. If you’re doing one hour of indirect activity for every two hours of direct work (most businesses are not that efficient), you have an overhead of 33%. If you take a third off the 2,000 hours, or about 667 hours, you’re now down to about 1,133 available hours.

Step 3: Divide Step 1 by Step 2

This will give you the breakeven point, which is the amount of money you need to charge each hour. If Step 1 was $50,000, and the time available was 1,133 hours, you would need to charge at least $45/hour for your time. That is your breakeven point, which becomes your secret number. This means that you will always charge something above that number or walk away from the job.

Step 4: Set a Fair Price

This is where reality sets in. Now that you know how much you need to be making, you can do some serious planning to achieve it—or relax because you’re already charging enough (it happens).

The first thing to do is to get over the shock if you discover that your breakeven point is a bigger number than expected. Some of your dreams may be unrealistic, but you now have the power to look at them and to decide whether to put them in a plan for later or admit that you don’t really need/want them. After all, you don’t have those things now, so it’s not like giving up something.

Similarly, maybe you have more time to make money than you allowed in the first draft of your plan. You could plan to work on Saturdays (like the owner of a retail store) and add 400 hours to your calculation. This is the point where you start to make those adjustments.

Avoid the temptation to cut your holidays or eliminate sick days; leave them in the calculation. If you don’t get sick, or you find yourself alone on a holiday with a job to do, the extra time you put in will be banking cash that you will need someday.

Be conservative and prudent. Remember, these are estimates, not hard figures. When doing your calculations, round up to the next higher dollar, even if it’s only one cent over an even number (e.g., for $44.01/hour, think $45/hour).

There are many other considerations that you can bring into the mix now. For example, if you’re charging well below your breakeven point, you need a strategy for boosting your rate back into a profitable range. You can learn strategies for raising your rates by joining ATA’s Business Practices Yahoo group and going through the old message threads. Once you have your breakeven point, I think that some of the books and articles you read will make more sense. Any “business” advice you receive that causes you to charge less than your breakeven point is nonsense.

In the range that most language mediators work, it would be reasonable to charge about $5 above your breakeven point. So, for example, if my breakeven point were close to what I’m charging now, I might charge $5-10 over the breakeven and then come back in six months to review how well my initial data looks.

Step 5: Setting a Piece Rate

Most professionals charge by the hour, but translators, potters, bootblacks, painters, fruit pickers, and many others must charge by the item. This is known as a “piece rate.” For translators in the U.S., the piece rate is customarily cents per word; elsewhere, it might be per line, per character, or per page. Converting the hourly price that you have set is a matter of knowing how fast you can work. That requires keeping track of your time as you work. Once you know your average speed, your piece rate becomes your hourly rate divided by the number of words (lines, characters, pages, etc.) that you translate on average. For example, if your hourly rate is $50/hour, and you translate on average 500 words per hour, then you should be charging at least 10¢/word.

You can do this exercise using your breakeven point (your secret number) to obtain the per-word rate below which you should be turning down the job. For example, if your breakeven point is $40 per hour and you translate 500 words per hour, your breakeven piece rate is 8¢/word.

Final Step: Have Fun

There are many reasons you might want to take a job below your price range—maybe even below your breakeven point. When you work below your breakeven point, however, know it for what it is: a pro bono, in-kind contribution to a charity or a church, a personal favor, a hobby, or an avocation. You’re not in business under these circumstances, but that doesn’t mean that what you do has no value. Armed with the breakeven point, you can make sound economic decisions for business or personal reasons. In either case, I hope that you always enjoy what you do.

Author bio

Jonathan T. Hine Jr, Scriptor Services LLC

Jonathan T. Hine Jr, Scriptor Services LLC

JT Hine translated his first book, a medical text, in 1962 and worked as a translator and escort interpreter through high school and a naval career. A graduate of the US Naval Academy (BS), the University of Oklahoma (MPA) and the University of Virginia (PhD), he is ATA-certified (I-E) and belongs to the National Capital Area Translators Association. He was the founding Secretary-Treasurer of the American Translation and Interpreting Studies Association.

When not writing his own books, he translates book-length fiction and non-fiction from Italian. More at https://jthine.com. Contact him at: jt@jthine.com

Jonathan Hine, whom I’ve followed since time immemorial, has guided my what-to-charge mindset since way, way back when I was a beginner. This short piece from an old Chronicle says it all. I’ve raised my rates pretty much every year. Maybe only half or one penny, but everything else goes up, why not my rates? Thank you, Jonathan for this clear exposition on the age old question of what to charge.