Fidelity In Translation

Reblogged from Dragon Translate blog, with permission from the author (incl. the images)

Faithfulness or fidelity has been a measure by which a translator’s work can be judged. However, fidelity has not remained constant throughout time and across space and at different stages of history the interpretation of fidelity has varied quite broadly. This essay aims to discuss this meandering in the term fidelity and will examine various theorists who can provide examples of fidelity in action.

Fidelity defines exactly how precisely a translated document conforms with its source. It can allude to how a document corresponds with its source in a variety of ways, from being ‘faithful to the message’, to being ‘faithful to the author’. Also one must factor in the register, the languages and grammar, the cultures and the form. Fidelity theory and its discussion has dominated the history of translation studies. In the early days, adherence to the source text in a verbatim way was seen as the best fidelity. However, as time has progressed, society has learned to define fidelity quite differently.

Origins of translators in history can be difficult to define. One of the key protagonists we have is Cicero, the early Roman orator. The Romans perceived themselves as a continuation of their Greek models. Translation was primarily a form of literary apprenticeship and literature was read in parallel Greek and Latin texts. Cicero outlines his approached to translation in his work De optimo genere oratorum (46 BCE), Cicero writes: ‘And I did not translate them as an interpreter, but as an orator, keeping the same ideas and forms, or as one might say, the ‘figures’ of thought, but in language which conforms to our usage. And in so doing, I did not hold it necessary to render word for word, but I preserved the general style and force of the language.’(Cicero 46 BCE). Thus Cicero was rebelling against the traditions of ‘word-for-word’ translation.

Another innovative translator from Cicero’s time was the poet, Horace (65 BC-8 BC), who again favored a ‘sense-for-sense’ view to translation. Horace was interested in promoting creative writing, and saw in his Ars Poetica how the free translation of Greek texts aided poetic composition:

‘It is difficult to treat a common matter in a way that is particular to you; and you would do better to turn a song of Troy into dramatic acts than to bring forth for the first time something unknown and unsung. Public material will be private property if you do not linger over the common and open way, and if you do not render word for word like a faithful translator [interpres] (Trans in Copeland 1991:29)

The ideas of Cicero and Horace have remained at the constant forefront of translator’s minds, even into the twentieth century:

‘During the 1920s, the philologist Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff urged translators of classical literature to “spurn the letter and follow the spirit” so as “to let the ancient poet speak to us clearly and in a manner as immediately intelligible as he did in his own time”.(Venuti 2012:73)

The ideas of Cicero and indeed Horace, in using ‘sense-for-sense’ fidelity, were taken up by the patron saint of translator’s, St Jerome (347-420 CE). The Edict of Milan in 315 was where the Emperor Constantine embraced the Christian religion for the Roman Empire and St. Jerome was responsible for the first official translations of the Bible into Latin, although this translation was never officially recognized by the Catholic church until 1546. Jerome quoted Cicero in a prominent letter he wrote to his friend, senator Pammachius in 395 CE: ‘Now I not only admit but freely announce that in translating from the Greek – except of course in the case of the Holy Scripture, where even the syntax contains a mystery – I render not word-for-word, but sense-for-sense.’ (St Jerome 395 CE)

Fidelity is a subject for which some paid with their lives, in particular when the translator was dealing with religious matters. It is that serious an issue and here are examples of some of translation’s martyrs.

Etienne Dolet (1509-1546) was a controversial figure in translation that fell foul to his age’s definitions of fidelity in translation. Dolet was indeed burnt at the stake after being condemned by the Sorbonne for his translation work whereby he denied the existence of the afterlife. He had added the phrase ‘rien du tout’ in an explanation of the afterlife in his translation work on one of Plato’s dialogues. This denial of afterlife contravened Church doctrine and was seen as blasphemous and heretical and so Dolet became one of translation’s first martyrs.

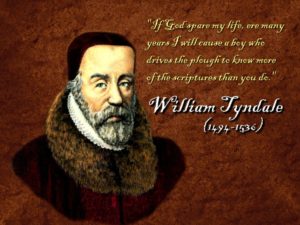

William Tyndale (1494–1536) was another translator who paid the ultimate price of execution after failing to submit to his era’s definitions of Fidelity. Tyndale’s heresy was to translate the Bible into English into an age where the use of the vernacular was frowned upon. The Tyndale Bible, in a later age where the parameters of fidelity had changed and there had been a paradigm shift, became the basis of the most famous Bible translation, the King James version.

Perhaps to have paid the ultimate price was harsh but it these were extreme cases in an age where the work of translators was so critical. The European Renaissance was flowered by the work of translators and it was part of the period whereby the work of the church clashed with the needs of the growingly enlightened populations.

‘Language and translation became the sites of a huge power struggle.’ (Munday 2012:37)

Moving on from the early translators and the Middle Ages, it wasn’t until quite late that the official views on fidelity moved away from word-for-word translation.

‘So, the concept of fidelity (or at least the translator who was fidus interpres, i.e. the ‘faithful interpreter’) had initially been dismissed as literal, word-for-word translation by Horace. Indeed, it was not until the end of the seventeenth century that fidelity had come to be generally identified with faithfulness to the meaning rather than the words of the author.’ (Munday, 2012:40)

John Dryden (1631-1700), the Poet Laureate, developed translation theories rooted in the free translation that flourished in the 17thcentury. His ideas and triadic model of translation fuelled the thinking of many subsequent translators, deep into the future. He developed three ideas, that of Metaphrase, Paraphrase and Imitation as providing the core elements of a translator’s task.

Dryden defines his views on fidelity:

‘I thought fit to steer betwixt the two extremes of paraphrase and literal translation; to keep as near my author as I could, without losing all his graces, the most eminent of which are the beauty of his words.’ Dryden (1697/1992:174 in Munday 2012:42)

In the early nineteenth century, German philosopher and translator Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768 – 1834), brought together a change in the ideology of fidelity. His views on domesticating and foreignization of texts introduced the concept of reader and writer and how the translator has a role of moving either towards each other.

For Schleiermacher, “the genuine translator is a writer ‘who wants to bring those two completely separated persons, his author and his reader, truly together, and who would like to bring the latter to an understanding and enjoyment of the former as correct and complete as possible without inviting him to leave the sphere of his mother tongue.’ (Lefevere 1977:74 in Venuti 2008:84)

Schleiermacher identified two possibilities for a translator: either move the source author text towards the reader, or move the reader towards the text. These were the outlines of his foreignization and domesticating strategies. His aims were produced by a desire to embellish the rapidly industrializing German economy into line with other superpowers with an embellishment of their mother tongue, in line with Nationalization movements. He wanted the German language to be enriched with a new vigor of translated ideas and words, to strengthen the German spirit and to make Germany a strong nation. A domesticated translation will favor the target tongue and culture and a foreignized translation will enrich and embellish vocabulary as it introduces alien ideas into the target language. Schleiermacher favored foreignization for this reason as he wanted the German language to be stronger and more akin to the industrialized economy that was developing during the period in his homeland. Fidelity for Schleiermacher became geographical. It depended on place and we are removed from the ideas of word-for-word and sense-for-sense and look to fidelity being a matter of space or place.

Schleiermacher has gone on to influence many modern translators and his foreignization and domestication theories have provided the roots of modern luminary Lawrence Venuti, whose own work has its own ideas on fidelity. Venuti looks at the ‘Invisibilty of Translators’and believes that transparency for a translator when he rewrites a text is essential for fidelity:

‘A translated text, whether prose or poetry, fiction or nonfiction, is judged acceptable by most publishers, reviewers and readers when it reads fluently, when the absence of any linguistic or stylistic peculiarities makes it seem transparent, giving the appearance that it reflects the foreign writer’s personality or intention or the essential meaning of the foreign text – the appearance in other words, that the translation is not in fact a translation, but the “original”.’ (Venuti 2008:1)

Thus, for Venuti, a translator must take the background and disappear. It is a concept which builds on moving the writer and reader together and apart and is an extension of more classical ideas of sense-for-sense and word-for-word theories. Not all modern day thinkers on translation share Venuti’s ideas on fidelity. Others can be more dark and critical of the whole translation experience.

After Babel is the seminal work from the 1970s by George Steiner. Steiner’s views on ‘Hermeneutic Motion’ are that translators face an impossible task. He values translators to a point but argues that translation is a harmful activity.

‘Fidelity is not literalism or any technical device for rendering ‘spirit’. The whole formulation, as we have found it over and over again in discussions of translation, is hopelessly vague. The translator, the exegetist, the reader is faithful to his text, makes his response responsible, only when he endeavors to restore the balance of forces, of integral presence, which his appropriate comprehension has disrupted. Fidelity is ethical, but also, in the full sense, economic.’ (Steiner 1998:318)

Thus for Steiner, he rejects ideas put forth by Cicero et al regarding sense-for-sense and also moves against Schleiermacher and Venuti. He recognizes fidelity as a concept but feels that the translator has a disruptive presence. It is in stark contrast to Venuti’s ideas on the translator being invisible.

It has been noted through the course of this essay how fidelity has changed over time and how the ideas of translators have not remained constant. Have these ideas always progressed? Can we ever move directly away from fidelity relating to ‘word-for-word’ renderings? A translator has a duty to remain faithful although innovation within any semantic field can be productive. It is the soul of a creative industry such as translation to think sometimes outside of the box, and such valuable paradigm shifts that progress education and the arts, that develop our whole culture, can only be possible when someone rises to stand out above the crowd, to put their neck on the line, and question the status quo. Not everyone succeeds when they do this, perhaps, but our histories are full of such philosophical giraffes and we remember the likes of Cicero, Horace, Schleiermacher, Dryden, Dolet, Tyndale, Venuti and Steiner, because they have progressed their fields by developing new ideas and pointing the work of translators in different, new directions. Yes, fidelity is an essential criterion for any translator, but it would be interesting to directly compare how much other terms in translation such as Loyalty, Equivalence and Function can also affect the work of translators. Perhaps that is a subject for future work.

Bibliography:

Copeland, R. 1991 Rhetoric, Hermeneutics, and Translation in the Middle Ages: Academic Traditions and Vernacular Texts, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

Hubbell, H. 1969 M., trans. “De Optimo Genere Oratorum.” Cicero: De Inventione, De Optimo Genere Oratorum, Topica. London: William Heinemann Ltd.

Lefevere, A. 1977 Translating Lierature: The German Tradition from Luther to Rosenzweig, Assen, Van Gorcum

Munday, Jeremy. 2012 Introducing Translation Studies. Oxon: Routledge.

Steiner, G 1998 After Babel: Aspects of Language and Translation Oxford: OUP

Venuti, Lawrence. 2008 The Translator’s Invisibility Oxon:Routledge

Venuti, Lawrence 2012 The Translation Studies Reader Oxon:Routledge