Savvy Diversification Series – The Role of the Genealogical Translator

The Savvy Newcomer team has been taking stock of the past year and finding that one key priority for many freelance translators and interpreters has been diversification. Offering multiple services in different sectors or to different clients can help steady us when storms come. Diversification can help us hedge against hard times.

With this in mind, we’ve invited a series of guest authors to write about the diversified service offerings that have helped their businesses to thrive, in the hopes of inspiring you to branch out into the new service offerings that may be right for you!

This post was originally published on the ATA French Language Division blog. It is reposted with permission.

My response to the question “what do you do?” tends to be a conversation stopper. I’m a professional genealogist and genealogical translator. Most people don’t have an idea of what either field entails. A professional genealogist or a professional translator might have some idea, but they’re usually missing part of the picture.

I usually begin by clearing up a few of the typical misconceptions. First of all, genealogy (the study of family history) isn’t a hobby for me, although I do trace my own family tree on occasion. In my professional genealogy career, I primarily do two kinds of work: research, in the form of tracing a client’s family tree, and teaching. While my post-secondary education in history gave me some background in genealogy, I’ve had to pursue extensive additional study to meet my clients’ and students’ needs. I current hold a Certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University’s Center for Professional Education and expect to complete a Certificate in Canadian Records from the National Institute for Genealogical Studies (Toronto, Canada) this Spring. I’ve also completed a number of non-certificate granting courses, including the Daughters of the American Revolution Genealogical Education Program. Genealogy is a tremendous amount of fun, but my business also represents a great deal of study and knowledge. Second, translation isn’t a hobby for me either! As the professional genealogy field is still developing its “rules” and “structure,” it is fairly easy for someone to call themselves a genealogist or a genealogical translator. This, unfortunately, has led to some people claiming to be professional translators who have had nothing beyond a high school study of the language. Thankfully, such individuals are rare – but they have impacted the reputation of the genealogical translator. Most, like me, have a mixture of exposure through daily life and formal education. I hold a BA in French Literature and have completed K-12 World Language teacher training.

If my listener has accepted my professionalism, their next question is often about genealogical translation and how it differs from typical translation. At first glance, genealogical translation seems simple. In most cases, all you’re doing is translating civil registration (what Americans call vital records) from French to English. Most employ standard sentence structure, so a translator is not faced with the literary complexity of a novel. But that understanding has missed a few important factors.

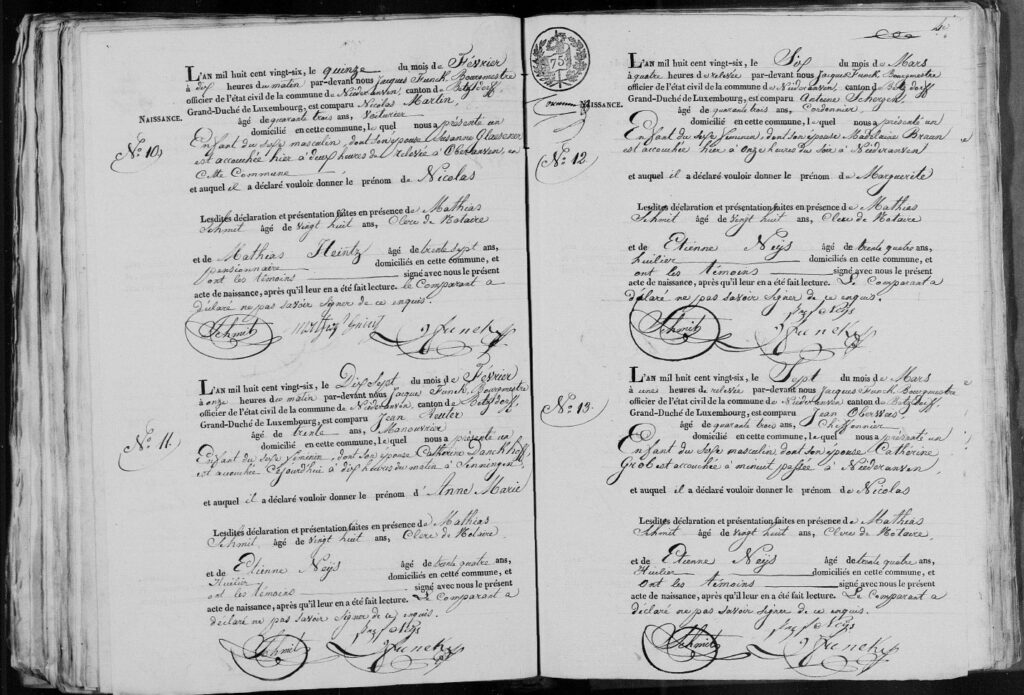

The first of these factors is the handwriting. Can you read the document below? This is actually on the easier side, as most of the document was printed. Whether you’re aware of it or not, handwriting and spelling have shifted dramatically over the centuries. An “ff” recorded in an older document is now read as “s.” A circonflexe in French word indicates the word originally contained an s — île was once isle. In fact, there’s a field dedicated to the study of the changes in writing, called paleography. To understand these changes, a genealogical translator either has to have read a number of historical documents or had formal training. Having both, as I have, is more typical.

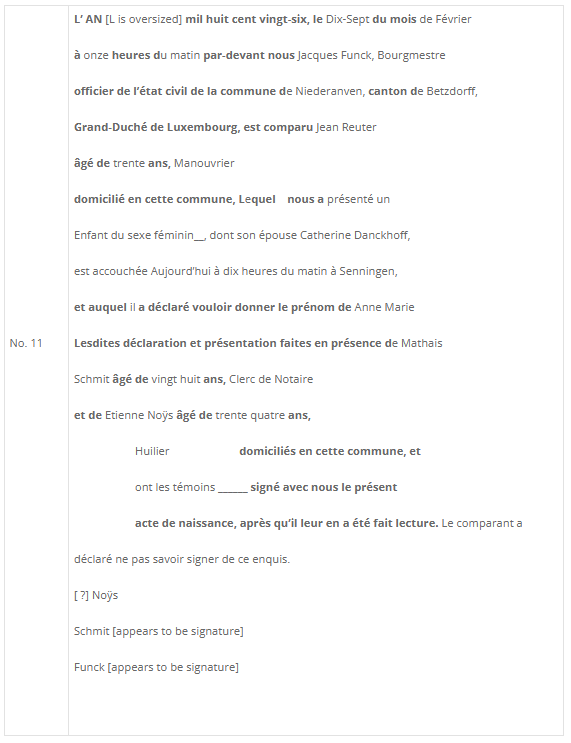

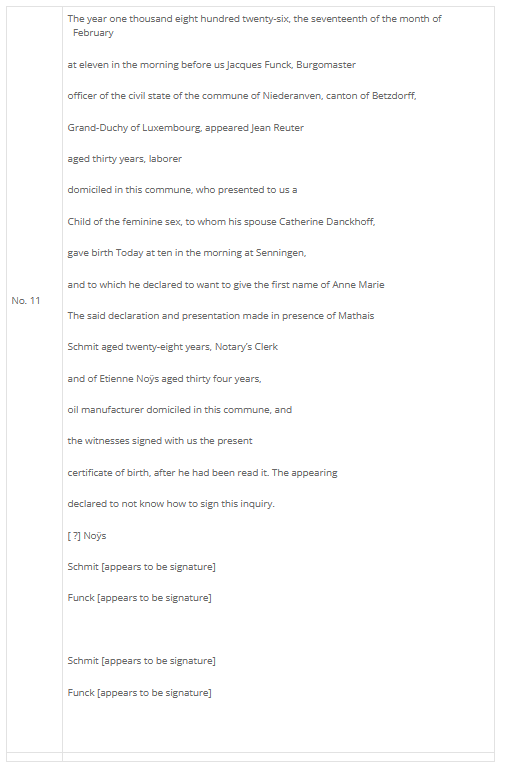

For those of you who were struggling, a transcription follows:

“Luxembourg, Civil Registration, 1662-1941,” images, FamilySearch (http://www.familysearch.org: accessed 5 February 2015), birth entry for Anne Marie Reuter, image 562; citing Niederanven, “Naissances 1796-1829.”

[Second entry on left side of the page. The entry is in two columns; the first is to the left of the body of the entry. Words in bold are preprinted]

After the handwriting, the next factor to consider is the language. Words are added and dropped from a language as new things are developed and older things disappear. Did “email” exist even thirty years ago? The above document is largely written in language a modern French speaker would recognize, but there is one exception: “huilier.” Most would be able to translate the word as “oiler” or “oil maker,” but do you know what it entails? Georgette Roussel indicates in the “Vieux Métiers“ section of the blog Familles de nos villages (http://famillesdenosvillages.chez-alice.fr/les_vieux_metiers_026.htm) that the huilier was responsible for taking the harvest to the mill and returning the oil to the village. Today, the person who controls the mill would have the title. A genealogical translator is responsible for recognizing and communicating the difference if it at all impacts the nature of the document.

Third, one must consider the document’s structure. While typical translation allows some fluidity in wording so that the document “reads naturally” in the target language, genealogical translation tends to be much more rigid in keeping the original structure. Why? Because the original structure can tell us something about the circumstances under which a document was created and offer details about your ancestor’s life. The format of the above cited document, a civil registration from Luxembourg, was regulated by law. A failure to use the word “épouse” can indicate that the couple was not married and may require additional research into their background.

In most circumstances, the genealogical translator would produce the following translation and stop, as their clients are controlling the direction of future research.

Yet, in other cases, in which they are acting as genealogical translator and genealogist, they would use the information contained within the document to pursue further research. In this case, we know Anne Marie Reuter’s parents were Catherine Danckhoff and Jean Reuter, aged 30, and that they were married. Finding their marriage certificate is a logical next step.

The role of the genealogical translator is often considered to be either confusing or deceptively simple. The reality is that my occupation is neither. It simply uses different set of rules than typical translation, requiring a greater awareness first, of the history behind the creation of the document and second, of the nuances of the document that must be conveyed in the target language. For a history lover fluent in a second language, genealogical translation can be a perfect fit.

About the author

Bryna O’Sullivan is a Connecticut-based French to English genealogical translator and professional genealogist.