One approach to preparing for ATA’s certification exam that has proven highly effective is working on short translations with colleagues in peer-based study groups.

ATA certification is one of the industry’s most respected and recognized credentials for translators. It’s also one of the only widely recognized measures of competence for translation in the U.S.1

To earn ATA certification, a translator must pass a challenging three-hour proctored in-person or online exam. The exam assesses the language skills of a professional translator, including comprehension of the source-language text, translation techniques, and writing in the target language. The current pass rate is less than 20%.2

One approach to preparing for the exam that has proven highly effective is working on short translations with colleagues in peer-based study groups. In the Spring of 2021, I decided to launch an initiative with members of ATA’s Spanish Language Division (SPD) and posted a message on the division’s listserv asking if there was any interest in forming a study group. The response was overwhelmingly positive, so I began researching approaches to organizing a large study group. I found a 2017 article in The ATA Chronicle by Maria Guzenko and Eugenia Tietz-Sokolskaya outlining the steps they took with members of the Slavic Languages Division to form and administer a peer-based study group3, and I’m very grateful to them for the suggestions. I also want to acknowledge interpreting colleague Rony Gao for his helpful guidance on organizing peer-based study groups.

Over 60 people responded to my initial inquiry on the SPD listserv. Gauging interest might be manageable for one person, but I knew successfully organizing a study group of that size would be a team effort. Due to the number of participants, a coordination team of five people was formed to help with organizing and administering the group, with four more people added later as organizational needs increased. We sent a survey (using Google Forms) to collect the particulars of each participant: name, email, education, work experience, ATA certification status, and their desired language direction in which to take the exam. It would have been good if we had also asked who had taken either a practice test or the actual exam.

What follows are the steps our coordination team took to form and administer the peer study group. Those wishing to form similar groups might find themselves following a different approach depending on various factors, including group size, language combinations, practice format, etc. Our approach was based on the following conditions: 1) we had a large number of participants, 2) we worked in only one language pair, and 3) our participants committed from the start to a six-month practice period.

Tools

One of the first decisions to be made was how to communicate within the study group. We found a number of free, easy-to-use cloud-based apps available for Mac, PC, and mobile devices.

- Communication (Slack, WhatsApp, email, etc.): We found email to be too cumbersome for a group this size. WhatsApp is ubiquitous and easy to use but lacks the feature richness of a proper business collaboration tool. We chose Slack because it has asynchronous communication for collaborating across different time zones, file uploading and sharing instead of email attachments, and third-party application integration.

- File Sharing (Google Drive, Dropbox, OneDrive, Box, etc.): We opted for Google Drive since it integrated better with some of the other tools we were using such as Google forms, docs, and sheets. That allowed us to post content (e.g., passages to be translated) in one location and then post the link in Slack.

- Video Conferencing (Zoom, Hangouts, Skype, Teams, etc.): Zoom was selected as a video conferencing tool because of its ubiquity. Organizational meetings were held with the coordination team, a kick-off meeting was held at the beginning of the study group program, followed by monthly group and other ad hoc meetings.

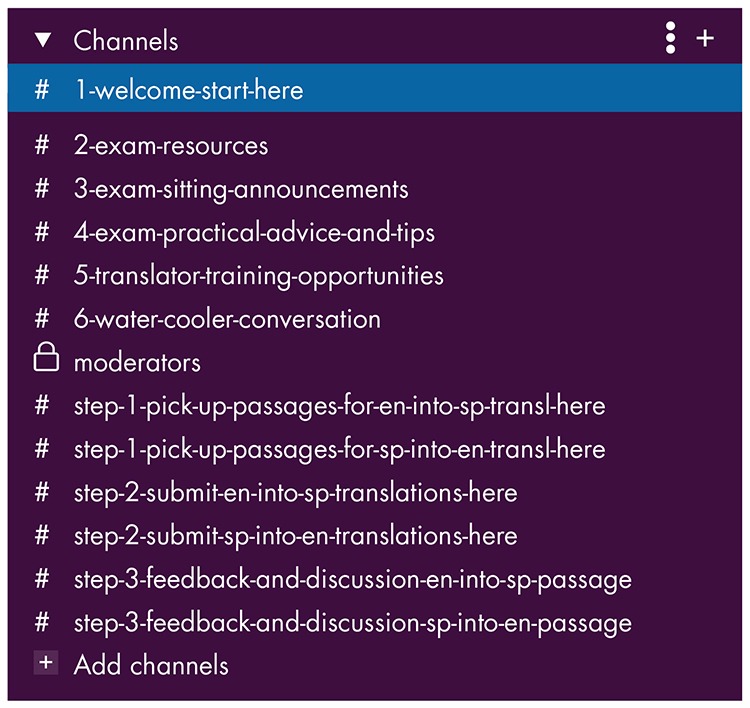

We created custom channels on Slack for posting exam resources, exam sitting announcements, translator training opportunities, water cooler conversations, a moderator channel, and a series of channels used for our translation feedback and discussion workflow. (See Figure 1.) Some participants had trouble setting up Slack or joining the necessary channels. Training videos from the Slack website were posted on a “welcome” channel. Some personalized training was also necessary to get everyone up to speed with the tool.

Figure 1: Custom Channels on Slack for Our Peer Study Group

Structure

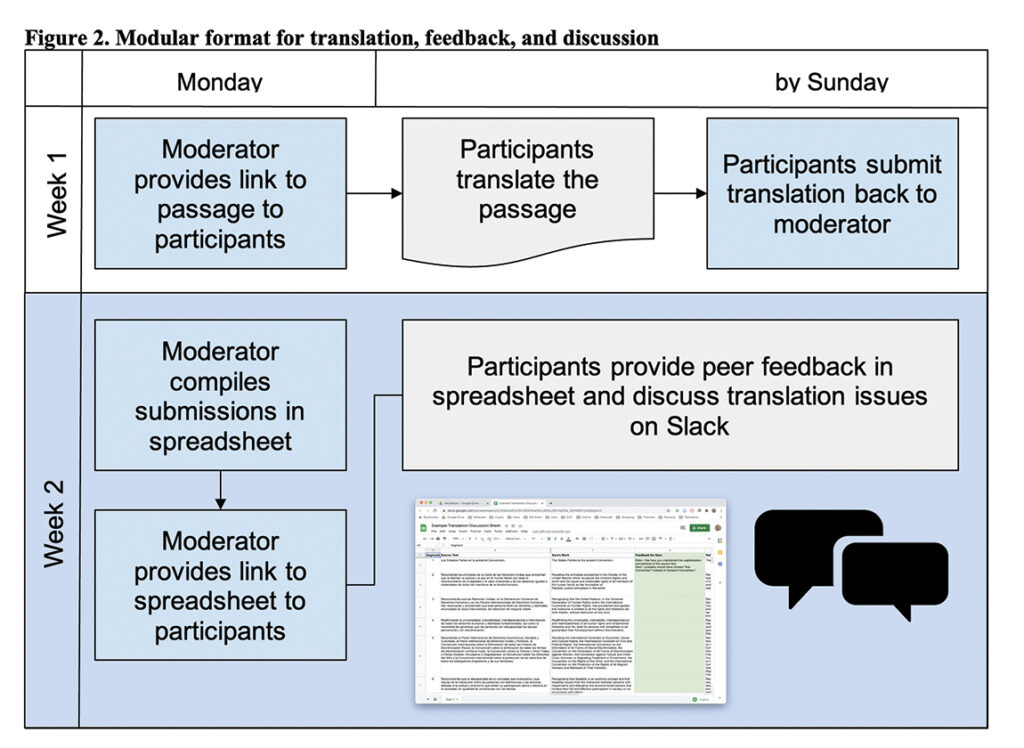

We used a two-week modular format: one week for translating the passage, and one week for feedback and discussion among group participants. (See Figure 2.)

Week 1: On Monday, the group moderator provided a link to the passage for the module. Group participants were given until Sunday to complete their translation and send it to the moderator, who then compiled the translations in a spreadsheet.

The first column of the spreadsheet contained the source-language text. Each participant had one column designated for their translation and one column designated for peers to provide written feedback. We found it advantageous to keep all translations for a given language direction together on a single sheet of the spreadsheet. However, we discovered that the sheet became difficult to navigate after 12-15 participants had been entered, so creating additional sheets is recommended.

Week 2: The moderator provided participants with a link to the feedback spreadsheet. Participant translation submissions were pasted in columns and a second adjacent column was left blank for feedback comments. Participants were expected to provide feedback on their peers’ translations pasted in the columns on either side of their own in the spreadsheet. Participants were also encouraged to discuss the passage and translation choices in Slack.

Selection of Passages for Translation

Passages were selected from online sources such as news articles and journals. An effort was made to duplicate the exam passage selection criteria used for ATA’s exam. Passages were generally 225 to 275 words. To be consistent with ATA’s certification practices, all passages were typically written at a university reading level but avoided “highly specialized terminology requiring research.” While they included terminology challenges, these could be met with “a good general dictionary.”4

Since ours was a six-month program, 12 sets of passages were selected for translation from English into Spanish and another 12 from Spanish into English. An effort was made to choose a wide variety of topics that would be challenging and represent a level of difficulty comparable to that of the exam without being overly technical or esoteric.

Figure 2. Modular Format for Translation, Feedback, and Discussion

Recommendations for Translation

We estimate 1.5 hours to complete the translation of a single passage. We recommend replicating the conditions for ATA’s exam as much as possible. This means completing the translation in one sitting. If taking the online exam is anticipated, we encourage participants to review ATA’s guidelines for the computerized exam.5 We also recommend encouraging participants to use the same laptop they’ll be using for the exam. Only resources that would be allowed during the exam are to be used.6 Another suggestion is to have participants take note of the areas of the translation where they feel confident and the areas where they feel unsure. This is a helpful way for partipcants to compare their self-assessment with the peer feedback they receive later.

Recommendations for Feedback and Discussion

We feel that the feedback and discussion part of this activity is one of the most beneficial components and one which cannot be done on your own. Coming together with peers is an opportunity for participants both to learn from others’ knowledge and to share their own. When reviewing a peer’s work, participants are encouraged to follow ATA’s error marking framework.7 Since this is a peer-based study group, participants are asked to focus their written feedback on substantive translation errors rather than stylistic issues that may not constitute errors. (See ATA’s website for an explanation of error categories.8) Various stylistic and other points can be discussed privately or as a group in the Slack channels.

Participant Engagement

We had 65 participants enrolled when we began the study group in May 2021. In general, we were able to maintain our schedule: one-week to translate and one week to comment and discuss. Pauses in the schedule were incorporated in conjunction with holidays. By the end of the sixth module, participation had diminished to a steady 12 to 15 participants per module in each language direction. This was true until the program ended in October 2021.

The following are some lessons learned:

- During the first two cycles, some participants realized that they either didn’t have the time to dedicate consistently to the group or were not otherwise ready to take the exam. Some discontinued their participation.

- To benefit from and contribute to a peer-based study group, participants should be expected to meet ATA’s minimum proficiency levels. For example, a passing grade on ATA’s exam is roughly equivalent to a minimum of Level 3 (Professional Performance) proficiency as described in the Interagency Language Roundtable’s ILR Skill Level Descriptions for Translation.9 Criteria may need to be established to verify language proficiency whether by educational achievements, independent testing, work experience, or a combination of these.

- Participants should be grouped in the feedback spreadsheet with those having similar work experience, education, or skill, since disparities can lead to inconsistent and sometimes unhelpful feedback.

- Participants should be encouraged to only work in one language direction at a time to ensure they have the time to dedicate consistently.

- Clear expectations need to be articulated from the beginning so all participants understand they must submit both translations and feedback on other participants’ translations.

- Some late enrollment was allowed, which proved to be challenging both for the participants and the coordination team. To avoid this, late enrollment should be discouraged when a program runs for several months. By comparison, ATA’s Slavic Languages Division runs its peer-based study group on a one-month cycle, but only if enough participants are enrolled to meet their minimum threshold.

Takeaways

An exit survey was conducted at the conclusion of the program with 30 participants responding. Questions were asked relating to time commitments, subject matter used for translation passages, general comments on feedback practices, technology tools, and whether or not their expectations were met.

The majority of participants completed between 10 and 11 modules out of a total of 12. While most participants were satisfied that the six-month program was an appropriate length, there was also significant interest in a shorter but more intensive two- to three-month program. A majority of participants found that Slack was a helpful tool for this type of study group. Interestingly, even after the initiative was completed, most participants were not sure if they would take the certification exam within the next six months. We’re happy to report that two of the group’s participants subsequently took the certification exam and passed.

Overall, the experience of this peer study group was gratifying and beneficial, especially for participants who stayed until the end. Many participants expressed interest in continuing with the study group, and anecdotally there seems to be an appetite for peer-based study groups. We hope the information presented here can serve as a model for any such future endeavors.

I would like to acknowledge the indispensable contributions of Angela Bustos, Erin Riddle, Michele Bantz, Deborah Bentolila-Hahn, Helena Senatore, and Rafael Treviño, both in administrating the study group and in preparing this article.

Notes

- “Guide to ATA Certification,” https://bit.ly/ATA-certificationguide.

- Ibid.

- Guzenko, Maria, and Eugenia Tietz-Sokolskaya. “Peer Reviewed: Collaborative Preparation for the Certification Exam,” The ATA Chronicle (September/October 2017), 38, https://bit.ly/Guzenko-Tietz-Sokolskaya.

- “About the ATA Certification Exam,” https://bit.ly/About-ATA-exam.

- See “Practical Tips for Taking ATA’s Certification Exam Online,” https://bit.ly/ATA-exam-tips, and Hansen, Michèle, “The Online Exam Is Here,” The ATA Chronicle (July/August 2021), https://bit.ly/Hansen-online-exam.

- See “ATA Computerized Exam Online Resource List: What’s Permitted and What’s Not,” tinyurl.com/ATAExamResources.

- “Framework for Standardized Error Marking, https://bit.ly/framework-errors and “Flowchart for Error Point Decisions,” https://bit.ly/flowchart-errors.

- “ATA Certification Exam: Explanation of Error Categories,” http://bit.ly/error-categories.

- The Interagency Language Roundtable is an unfunded federal organization. It’s where government employees interested in languages can come together with counterparts inside and outside government to discuss and share information and address concerns. See: https://bit.ly/ILR-about.

Jason Knapp is a freelance interpreter and translator and the owner of Knapp Language Services, LLC. He specializes in the translation of legal, medical, manufacturing, and construction subject matter. He is certified as a court interpreter in California, Colorado, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, and Oregon. He is also certified as a medical interpreter for Spanish through the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters. He has a post-graduate certificate in conference interpreting from the Universidad del Salvador. jason@knapplanguageservices.com